| Unintended Consequences |

|

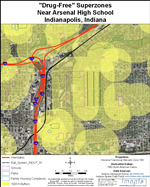

The op-ed article below was written by the four students at DePauw who were the first to become interested in and testify on drug-free zones in Indiana. Legislation Creating Drug-Free Zones Has Unintended Consequences by Keelin Kelly, Curtis Moore, Rebecca Murphy and Megan Tucker-Hall These unintended consequences stem from the bill's creation of overlapping zones that encompass entire communities in urban areas, but not in suburban and rural areas. Therefore, we oppose this bill because it punishes people unequally based solely on their geographic location. In rural areas, the bill does what it is intended to do. Current drug-free zones keep drug dealers away from schools, parks, and housing developments because they affect only those areas and not the vast majority of the county. However, in Marion County and other urban areas, schools, parks, youth programs and especially churches exist in such high density that the law would create vast overlapping zones that encompass entire neighborhoods and communities. It would also create the anomalous situation where people possessing drugs in their private residence would be subject to the penalties of a Class A felony simply because they are three city blocks from a church. Because inner cities are disproportionately inhabited by blacks and Hispanics, the bill would also have much greater effect on racial minorities. Other states have found that drug-free zones primarily target minorities. For example, New Jersey's State Sentencing Commission found that 96 percent of prisoners serving time for drug-free zone offenses were either black or Hispanic, which is far out of proportion to their rate of illicit drug use. Contrary to popular belief, white Americans have the same rate of illicit drug use as black and Hispanic Americans. In fact, the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 24 percent of white teenagers from the ages of 12-17 used illicit drugs in the past year, which is substantially higher than the rate for black teenagers, 19 percent. Indiana needs to take a comprehensive look at the effects of existing drug-free zones before establishing new ones. The original intent of drug-free zones was to deter drug dealing near schools and our youth. Over the years, the legislature has created so many additional overlapping drug-free zones that the law no longer protects our schools and youth, thus deviating from the law's original purpose. Examining studies other states have completed and compiling information about Indiana will help us remedy this problem. The goal of this legislation should be to administer justice to drug offenders without regard to geographical location or ethnic background.

|