| Testimony | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On October 8, 2008, Kelsey Kauffman, Ryan Keeley and Becky Murphy provided the following testimony (including linked maps) before the Indiana Sentencing Policy Study Committee about Drug Free Zones and Sex Offender Exclusion Zones.

The Sentencing Policy Study Committee is an interim committee established by the legislature to review criminal sentencing in Indiana. Its members consist of eight legislators (four each from the Indiana Senate and House of Representatives), the Chief Justice of the Indiana Supreme Court, several lower court judges, the commissioner of the Indiana Department of Correction, and representatives of various criminal justice agencies. We were invited to speak before this committee on the basis of testimony previously presented in 2007 and 2008 before the Indiana Senate Committee on Corrections, Criminal, and Civil Matters regarding bills that would have extended drug free zones (to include churches and marked bus stops) and sex offender exclusion zones (to include child care centers).

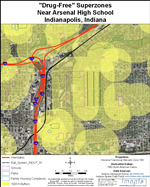

Testimony Before the Sentencing Policy Study Committee Kelsey Kauffman Every few years, I teach a winter term course on Prisons and Public Policy. Among the requirements is that students choose a bill currently under consideration by the General Assembly that affects prisons, research it, decide if they are for it, against it, or want it amended, and then testify for 90 seconds before a legislative committee. In January 2007, four students (including Becky Murphy who is seated to my right) chose Senate Bill 3, which would have extended “drug free zones” [DFZs] to include churches, and the related House Bill 1267, which would have extended DFZs to all marked bus stops. Using DePauw’s GIS center, they created the forerunners of the maps we just passed out. Last spring, Ryan Keeley (to my left) created related maps that showed “Sex Offender Exclusion Zones” [SOEZs] both as they exist today and how they would look if child care centers were added, as was proposed in House Bill 1134. During debate over that bill, Senator Bray suggested that this body consider the maps and how the zones might be refined. The purpose of both DFZs and SOEZs is to protect children from drugs and sex offenders. The idea is that drug dealers and sex offenders will know where the zones are and will make a rational choice to avoid them due to the special penalties imposed for being inside them. However, if they don’t know where the zones are, or if the zones are so large and so numerous that they blanket entire neighborhoods and communities, then the effectiveness of the zones is undermined. Potential problems with both DFZs and Sex Offender Zones arise more frequently in urban areas than in rural areas. Thus, in creating the maps, my students have focused on Marion County. Becky Murphy Please look at the first map. Indiana statute currently establishes 1,000-foot DFZs around school properties, public parks, family housing complexes and youth program centers. Map 1 shows the existing zones around schools, parks and housing complexes in Marion County, but not “youth programs.” Neither we nor, we assume, most drug dealers could determine exactly what constitutes a youth program center, much less locate all of them in Indianapolis.* As you can see from Map 1, the zones are so large and so numerous that they blanket entire areas. Maps 2 – 4 and 5 – 7, which are stapled together, provide close-ups of the areas around Arsenal High School to the east of us and Crispus Attucks and the Zoo to the west of us. The top map of each set shows the zones as they exist today—so numerous and overlapping that few places exist outside the zones. These two sets of maps illustrate a second problem. The zones are frequently intersected by highways, rivers, railroad tracks and other natural and man-made barriers, which, by themselves, cut off access to children. Look, for example, at the bottom of map 5. We put an arrow next to Thomas Edison Middle School, which is bordered on the east by the White River, and on the south by I-70. Yet, a drug dealer on the far side of the river or of the interstate (or traveling on the interstate itself) is still considered to be within that school’s DFZ. Ryan Keeley The 4 maps that are stapled to maps 2 and 5 illustrate one way to diminish these unintended consequences, which is simply to shrink the size of the zones. One thousand feet is a long ways—the equivalent of three football fields end-to-end, or three city blocks. You can barely see someone that far away. A circle with a radius of 1,000 feet around a single point encompasses 3,140,000 square feet—so large that you could fit the equivalent of 68 football fields inside it. Yet even that underestimates the size of most DFZs because most schools and parks have considerable area themselves. For example, we estimate Arsenal High School and playing fields have an area of around 3,000,000 square feet. Add a 1,000 foot zone all the way around it and your drug free zone is a massive 14 million square feet. The second map in each set of three, Maps 3 and 6, show what would happen if you shrank the size of the zones around schools to 500 feet and around parks and housing complexes to 100 feet. The third map in each set, Maps 4 and 7, shrink all the zones to 100 feet. Not only do the superzones quickly disappear, but so does the problem of natural or man-made barriers intersecting the zones. Becky Murphy As you know, large racial disparities exist in who goes to prison for drug dealing in Indiana as elsewhere, yet US Department of Justice data suggest that blacks, whites and Hispanics use illicit drugs at roughly the same rates. We found that over the past two decades, a black man in Indiana is 18 times more likely than a white man to be in prison for drug dealing. We looked to see if DFZs may be contributing to these disparities. The background to Map #1 shows density of black and Hispanic population in Marion County. That black and Hispanic neighborhoods tend to be within DFZs is, of course, an unintended consequence of the statute, but the effect is substantial nonetheless. One of the reasons my classmates and I opposed extending DFZs to churches is because adding them would have meant that virtually all neighborhoods with substantial minority populations would have been within a DFZ. The Department of Correction provided us data on every inmate who was serving time in 2007 for a Felony A or B conviction for dealing Schedule 1 drugs. Table 1 presents the breakdown for Marion County by felony level, race and gender. Table 1: DOC inmates in 2007 who were convicted in Marion County of Felony A or B drug dealing, by felony level, race and gender Felony A

Felony B

During the summer of 2007, I looked in detail at every file that was available in the Marion County Records Office for individuals convicted of A or B felonies for Schedule 1 drugs, except for black males convicted of B felonies. They were so numerous that I selected only a subset of that group. The final map in your packet, which is very much a work-in-progress, shows location of arrests by race and gender. Again, it greatly underestimates the number of B felonies for black males. Not surprisingly, it shows that blacks are dealing drugs in their own neighborhoods—which are more likely to be within DFZs, while whites are more likely to be dealing drugs in their own neighborhoods, which are less likely to be within such zones. Ryan Keeley Sex Offender Residency Restrictions under IC 35-42-4-11 create zones similar to the DFZs. Map 8 is the same as the first DFZ map except that “housing complexes” are excluded and the background is population density, not race data. Map 9 shows what happens if you add the 760 childcare facilities registered in Marion County. Maps 10 & 11 are a close-up of a neighborhood near Speedway. Map 10 shows zones of various sizes around schools and parks, while Map 11 adds childcare facilities. As with the DFZ maps, and for the same reasons, we haven’t tried to locate “youth program centers.” We assume that childcare facilities are something other than youth programs because of the bill last session that sought to add childcare facilities to the Sex Offender Residency Restrictions statute, but it remains unclear to us whether or not childcare facilities could fall under the label of youth programs. The same problems emerge with the Sex Offender Zones as with the DFZ. The central problem that directly arises from the large size and number of zones is the creation of superzones. In Miami, sex offender exclusion zones are so numerous and so large that the only place sex offenders can live is under one highway overpass, thus forcing most sex offenders either into rural areas or into hiding. Other problems are that, unlike schools and parks, youth programs (and childcare facilities) can be transient. As well, most people don’t know where these facilities are, so it is hard to avoid them. Kelsey Kauffman In order for zones to fulfill their mission of providing special protection for children they need to be clearly defined, easily identifiable, and limited in number so that they stand out from the surrounding communities. We recommend that the Sentencing Policy Study Committee consider the following: 1) Shrink the size of the zones to 500, 250 or even 100 feet to eliminate superzones; 2) Limit the zones to contiguous property immediately surrounding protected areas; 3) Require clear demarcation of zones so that offenders can make rational choices to avoid them; 4) Eliminate existing zones around youth programs and avoid creation of future zones around entities such as child care facilities, marked bus stops and churches that are so numerous as to cover entire urban areas. It is the uniqueness of the zones that best protects children not their ubiquity.

“Youth program” is defined under IC 35-41-1-29 as a “building or structure that on a regular basis provides recreational, vocational, academic, social, or other programs or services for persons less than eighteen (18) years of age.”

|